Balsamorhiza sagittata is a perennial herb belonging to the Asteraceae (Sunflower) family. The genus name is based on the Greek word for balsam and rhiza, alluding to the thick root with a sticky, balsam-like resin in the bark. The specific epithet “sagittata” refers to the arrowhead-shaped leaves (Canadian Botanical 2002). It is widespread across western Canada and much of the western United States. A specimen was collected by explorer and botanist Meriwether Lewis near Lewis and Clark Pass in 1806 (Wikopedia n.d.)

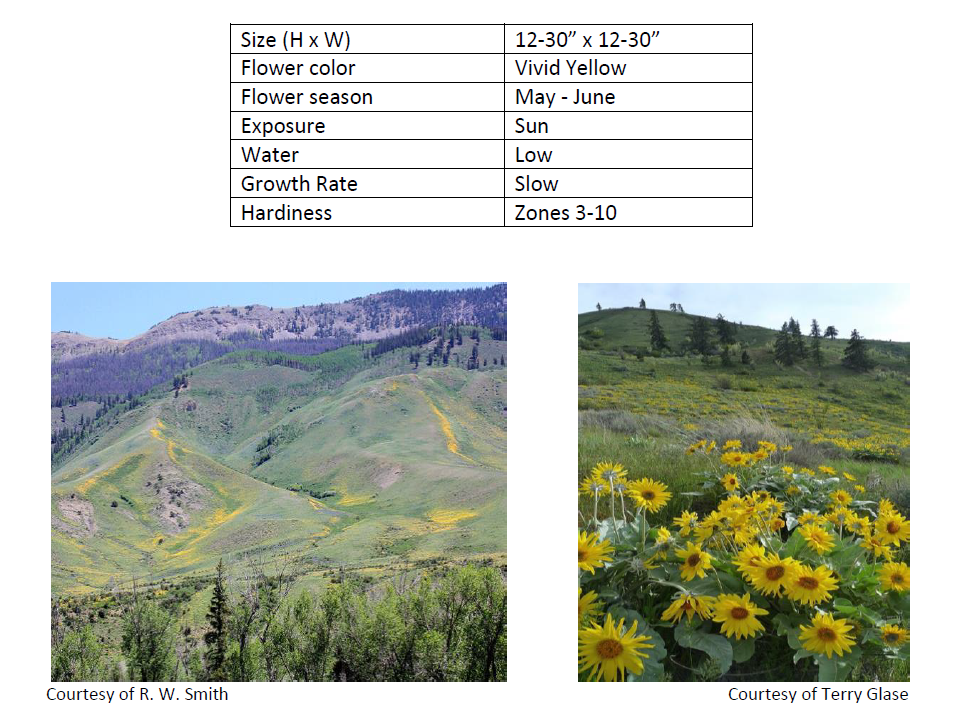

Culture: An attractive and native western North America spring perennial, the plant is common in cold, dry areas of the West. It may be found most abundantly in sunny, south facing open slopes and mountain fields, but it can also be a common plant in the understory of sandy open conifer forests. Most abundant in deep, well-drained fine to medium soils with a pH of 6.5-8.0, it can also be found on gravel to clay soils (USDA). It grows best in full sun, but it can take less sun, with the result of less flowers. Once established, B. sagittata is very drought tolerant. It is commonly associated with shrub steppes, sagebrush communities growing among grasslands, ponderosa forests and prairie meadows growing from low to middle elevations. Because of the deep taproot, B. sagittata tolerates fire, grazing, trampling and drought. The plants are very slow growing and may take 3 to 5 years to reach full production and will live 40 years or more (count the leaves for an approximation of age) (Wenatchee 2020).

An eagerly awaited, spectacular wildflower, it appears early in the spring (1 week after the snow is off!) from a branched, thickened, woody, resinous tap-root with a pleasant balsam odor. The bark-covered root (the width of a hand) may extend well over 8’ deep into the soil. This helps the plant to find moisture on warm, dry hillsides. The root is crowned by numerous dark-grey dried leaf and flower stalks of former years with this year’s new shoots popping through. Growing from a basal clump, the large, sagittate, silvery basal leaves are hairy, and large, approaching 20”. The ascending upper stem leaves are smaller, linear to elliptic, and minutely glandular and pubescent. After new shoots appear, the plant gives rise to several 8-24” tall, hairy, glandular almost leafless stems each bearing a solitary flower at the top. B. sagittata is seen very early in the spring and up until early summer when it dies back and goes dormant. In a meadow setting, the plant could be combined with Erythroniums (Dog’s Tooth Violets), Lavender Lupines, or, Liatris spicata (Dense Blazing Star).

Flowers: Large showy blooms, May to June. The vivid yellow, sunflower-like, inflorescence bears one flower head arising from the basal clump to a height of 6-31”. Each inflorescence sits upon a dull green woolly bract and is made up of fertile, monoecious, disc and ray flowers (E-Flora 2020). The bright yellow ray florets are each up to 1.5” long and completely ring the disc. The center golden disc florets have a long tubular stamen sitting well upright and above the petals for easy access by pollinators. The inflorescence is insect, bee, and wind pollinated. The fruit is a glabrous achene about 1/3” long that is wind dispersed.

Noteworthy Characteristics: Under the name Okanagan Sunflower, it is the official flower emblem of the City of Kelowna, British Columbia (my home town) (Kelowna Now 2015).

Faunal Associations: Provides good spring and summer forage for sheep, deer, elk, big game and fair for grazing cattle and horses (young tissues of the plant contain nearly 30% protein) (USDA 2020). The animals find the plant palatable, especially the flowers and developing seed heads. The seeds feed rodents and birds. All portions of the plant, except the coarser stalks, are eaten. The plant is much more palatable during the spring and early summer, becoming more tough and dry later in the year (United States Forest Service 2020). The flowers provide ample pollen and provide food for pollinators early in the season, especially bumble bees (University of Texas 2020.). Insect damage can be significant.

Maintenance: This plant is a natural wildflower and should not require any maintenance. Do not dig this plant up in the wild. It is very competitive against weeds and should never be fertilized. By blooming and completing most of its growth in the spring, balsamroot avoids the dry, hot months of summer. After blooming, the plant begins to wither, the large leaves drying up and becoming crisp and brown; after which the plants are dormant and easy to miss - you wouldn’t even know they had been there. In regions where summer’s heat and dryness can be as much of a challenge as winter’s cold, both blooming early and growing a thick taproot (better to reach and store moisture) are adaptations that allow the balsamroot to thrive (At the Edge 2015). Because the taproot reaches deep into the soil, B. sagittata may be considered to help stabilize slopes and prevent erosion. The species is believed to have potential for use in oil shale, roadside and mining restoration practices, although attempts to seed outside of its natural area of occurrence have been largely unsuccessful (USDA 2020)

Propagation: Because the plant is a slow-growing species, production and use of transplant materials for seed production and in wildland settings is appealing, however, reports suggest that successful establishment from transplanting bareroot or wilding stock is low (US Dept of Interior 2018). The plant takes poorly to propagation; thus, seeds only should be used for propagation. Plant the seeds in the fall, 1/2” deep, in full sun and well-drained soil. Sow rather thickly as germination rates will be low (Everwilde 2020). The seeds require a prolonged (3 months) cool, moist stratification and then incubation at cold temperatures for germination. Better to plant the seeds in the fall to take full advantage of the winter stratification (Journal 1979). Again, spring division is very difficult due to the tough, bark covered tap root.

Ethnobotany: Coming into season in early spring, nearly all parts of this plant were used as food by various Indigenous peoples. The starchy roots, harvested in late autumn, could be baked, boiled, or steamed and eaten, as well as the young shoots (the root could be used as a coffee substitute). The immature flower stems could be peeled and eaten. The nutritious and oil-rich seeds (particularly valuable as food, flour, or used for oil) were also used (US Forest 2020). The plant can be bitter and pine-like in taste. The leaves are best collected when young and can carry a citrus flavor. Root infusions were used by Indigenous people to treat a variety of complaints, especially stomach problems, fevers, whooping cough, urinary aid and tuberculosis. Root decoctions were also used for headaches, rheumatism, venereal disease, and as an eyewash and birthing aid (USDA 2020). The large hairy leaves can be used as an insulation in shoes to keep the feet warm (Natural 2020). A poultice made from the coarse, large leaves has been used to treat severe burns (Plants For A Future 2020).

Legend & Lore: Local folklore says that when the balsamroot blooms, it is time for the rattlesnakes to come out of their winter dens (At the Edge). Arrow-leaved balsamroot is featured in a prayer that the Nlaka’pamux of British Columbia addressed to the Sunflower-Root when it was harvested: “I inform thee that I intend to eat thee. May thou always help me to ascent, so that I may always be able to reach the tops of mountains, and may I never be clumsy! I ask this from thee, Sunflower-Root. Thou art greatest of all in mystery.” Failure to recite this prayer before eating was said to make the person partaking of the food lazy (Canadian Botanical 2002).

Several rituals relating to harvesting and processing of Arrow-leaved balsamroot have been documented. Nlaka’pamux women had to abstain from sexual intercourse during the season of root harvest. A man was not to come near the cooking pit while the roots were being cooked. Women painted their faces red, or painted a large black or red spot on each cheek before harvesting the roots. There were taboos against a bereaved spouse eating Arrow-leaved balsamroot for a whole year after bereavement. The leaves were used in puberty rituals for girls (Canadian Botanical 2002).

References:

- At the Edge of the Ordinary, 2015. Mingo, Heather M. http://edgeoftheordinary.wordpress.com (accessed November 25, 2020).

- Canadian Botanical Association Bulletin, Nov. 2002. http://www.cba-abc.ca (accessed November 25, 2020).

- E-Flora BC: Electronic Atlas of the Flora of British Columbia, Department of Geography, University of British Columbia, 2020. https://linnet.geog.ubc.ca/biodiversity/eflora/index.html (accessed November 25, 2020).

- Everwilde Farms Inc., Wisconsin, 2020. http://everwilde.com (accessed November 25, 2020).

- Journal of Range Management “32(1)”, January 1979. Young, James A. and Raymond A. Evans. https://www.semanticscholar.org/ (accessed November 25, 2020).

- Kelowna NOW Newspaper, Hjalmarson, Lauren, 2015. http://kelownanow.com (accessed November 25, 2020).

- Natural Medicinal Herbs, 2020. http://naturalmedicinalherbs.net (accessed November 25, 2020).

- Plants for A Future, 2020. http://pfaf.org (accessed November 25, 2020).

- United States Department of Agriculture, 2020. http://plants.usda.gov (accessed November 25, 2020).

- United States Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, 2018. http://blm.gov (accessed November 25, 2020).

- United States Forest Service, USDA, 2020. https://www.fs.usda.gov/managing-land/wildflowers (accessed November 25, 2020).

- University of Texas at Austin, “Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center”, 2020. http://www.wildflower.org (accessed Nov 25, 2020).

- Wenatchee Naturalist, Ballinger, Susan, 2020. https://www.wenatcheenaturalist.com/ (accessed November 26, 2020).

- Wikopedia, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Main_Page (accessed November 25, 2020).