By now, if you have saved any leaves that fell from your trees last fall, they will be mulch around your precious perennials or your tree trunks or your hard-hit-by-this-winter’s-freezing-spells evergreen shrubs, shrubs that may have given up the ghost. Luckily for me, the leaves I saved from November 2023 are not mulch, but instead are scans in my computer. Granted the leaf images are a little blurry here and there, but they’re still identifiable.

I use Latin names of the tree species so as to create alphabetical order. And then I use this order—(1) simple leaves without teeth, (2) leaves with teeth, (3) leaves with lobes, (4) compound leaves—to create more order.

As Robert Macfarlane says in The Lost Words, the name of something can be “a spell that evokes the spirit of the creature it attaches to.”(1) Once we know the name of a tree, we recognize that tree, care more about it, and then we take better care of it. So here goes, to describe these long-ago fallen leaves and the trees they came from.

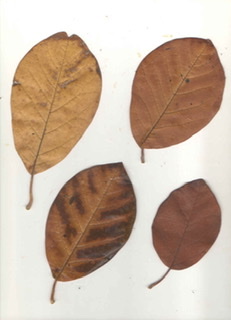

First are the simple, brown to chestnut-coloured leaves of Magnolia sieboldii. They are oval and have entire margins, meaning no teeth. This species is planted less often than other ornamental magnolias, has fewer flowers than most magnolias, and its white flowers almost hide, by hanging down.

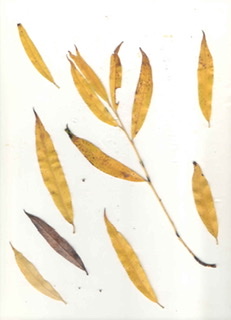

The slim, lanceolate, yellow leaves of a willow are recognizable by their yellow stems to be the cultivar, Salix ‘Chrysocoma’. Most of these leaves have already fallen from their stem, though they were together when I picked them up from the ground. The slim lance-shaped leaves hang down, providing the weeping effect of this willow, so much part of these trees’ appeal.

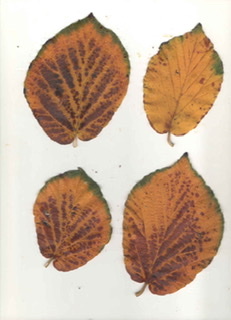

The leaves of Hamamelis virginiana, common witchhazel, are next. Their margins are not entire, having edges that are wrinkled, slightly crenate and slightly toothed. These leaves are quite thick, edged with green, and strongly veined with dark brown flecks taking over the spaces between veins. The stalks—petioles—are short and curved, keeping the leaves close to the branch. Blooming in winter with most unusual flowers of yellow ribbons, this treelike shrub is one of my favourites.

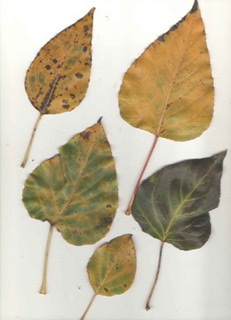

Next are the leaves of Populus trichocarpa, a tree commonly known as black cottonwood, black poplar, and western balsam poplar. It’s in Salicaceae, the willow family. This is one of the many poplars that surrounds its seeds with “cotton” so the wind may disperse them more easily. Native to the Pacific Northwest, black cottonwood is a tall tree that also grows suckers, just in case its seed dispersal method of propagation is insufficient. The bases of these leaves are each shaped differently, some flat and some rounded, and the leaves are coloured differently, including yellow, blotched, and dark green. They smell of turpentine and various parts of the tree were used medicinally by First Nations.

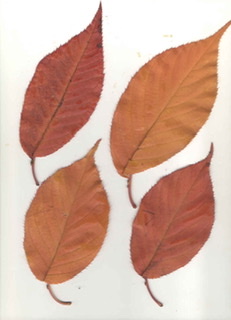

The popularity of ornamental cherry blossoms on this West Coast of British Columbia could make us forget how beautiful these trees can look in fall when their leaves turn apricot, salmon, and orange colours before falling. These toothed leaves have curved petioles and pointed tips. If you look carefully at the leaf stalks, you will be able to see the petiolar glands; these secrete a nectar that attracts beneficial insects to protect the tree from pests. This particular tree is in the Prunus Sato Zakura Group, being an ornamental cherry whose crossbred history is lost in the history of Japanese village cherry tree horticulture. And now I don’t know under which tree I collected these trees from, but I’ll guess it was a Kanzan, the one that blooms very late in the season and bears many shocking-pink multi-petalled blossoms

The next tree grows outside my front door, a 23-year-old street tree, Liquidambar styraciflua, American sweetgum. (Did you know you can look up the trees that are growing on your street? Go to https://opendata.vancouver.ca/explore/dataset/street-trees.) It’s in Hamamelidaceae, the witchhazel family, the second in this family in this article. These lobed leaves are palmate—shaped like a palm—in that the five lobes emerge from the point where the petiole joins the blade. The larger yellow leaf has flecks of photosynthesizing green left. The smaller leaf is brick red and three of the lobes have additional lobes on them. So the leaves are dimorphic: in two distinct forms.

The next two leaves are copper-coloured and have four lobes, a most unusual number of lobes for a plant leaf. The unusualness of this feature is commemorated in the song, “I’m looking over a four- leaf clover.” The fallen four-lobed leaves are from Liriodendron tulipifera, a tall oval tree commonly known as the tuliptree because of the resemblance of its flowers to tulips. These leaves make the tree easily identifiable, though it’s a little trickier to differentiate between Liriodendron tulipifera and its relative Liriodendron chinese. In this case, texture is the differentiating feature: the Chinese tuliptree leaf feels smooth whereas the western one feels rough, coarse.

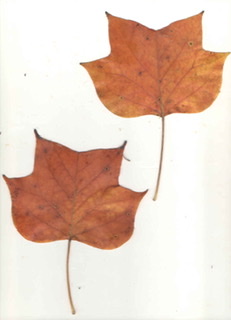

Here are two leaves that people often guess are from a maple tree, but in fact are from the London plane tree, Platanus x hispanica, a superb urban tree, superb because it tolerates urban pollution extremely well. The way to tell the difference between a palmate maple leaf and a London plane leaf is by looking carefully at their venation. Three veins emerge from the petiole in the London plane and these lead to three lobes that have additional lobes on them. At first glance, the leaf looks as though it is palmate, but noticing there are three veins rather than five will set you straight.

The next three scans of leaves are from oak trees. The first is Quercus robur, English oak. Then Q. rubra, red oak. Finally a hybrid that is actually an evergreen oak, Q. x turneri, Turner’s oak, a cross between Q. ilex (an evergreen) and Q. robur. English oak and Turner’s oak are quite similar, except that the leaves from Turner’s oak are still quite green. The red oak leaves have seven or more lobes, separated by deep sinuses. And of course red oak leaves are much bigger than the others.

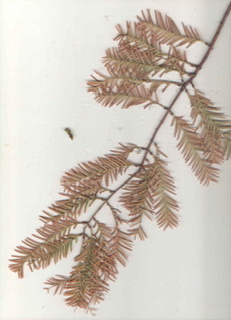

Finally, there is a fallen branch of Metasequoia glyptostroboides, dawn redwood. The entire scientific name of this living fossil means “this tree is like this and like that, but is something else again.” Metasequoia means it is like a sequoia, but not; and glyptostroboides means it is like a tree in the Glyptostrobus genus, but is not one. It just shows the struggle that plant hunters endure to recognize differences between plants. Dawn redwood is a deciduous conifer, an unusual combination. The leaves are bipinnately compound, the pairs of leaves growing opposite each other. The small elements on each leaflet are slim, short needles.

I’ve called this piece “So Much for Mulch” because a title is essential for differentiating one piece of writing from another. But so is mulch essential for cooling and protecting the soil around your plant, for retaining moisture in the soil, be it rain, snow, or a sprinkler, and for keeping the soil’s seedbank from spreading weeds. Much can be done with mulch.

Text and photos by 🌱VMG Nina S

(i)Robert Macfarlane first writes about this spell, but the quoted words come from Dave Goulson’s Silent Earth.